Hi Friends,

There’s no easy way for me to break this news to you: I’m now sending emails.

As I consolidate my practice, I feel that this is an important way for me to keep in touch and share what I’m doing. You’re on this first email because we have shared some art experience in the past. This post was originally sent out as an email a few weeks ago.

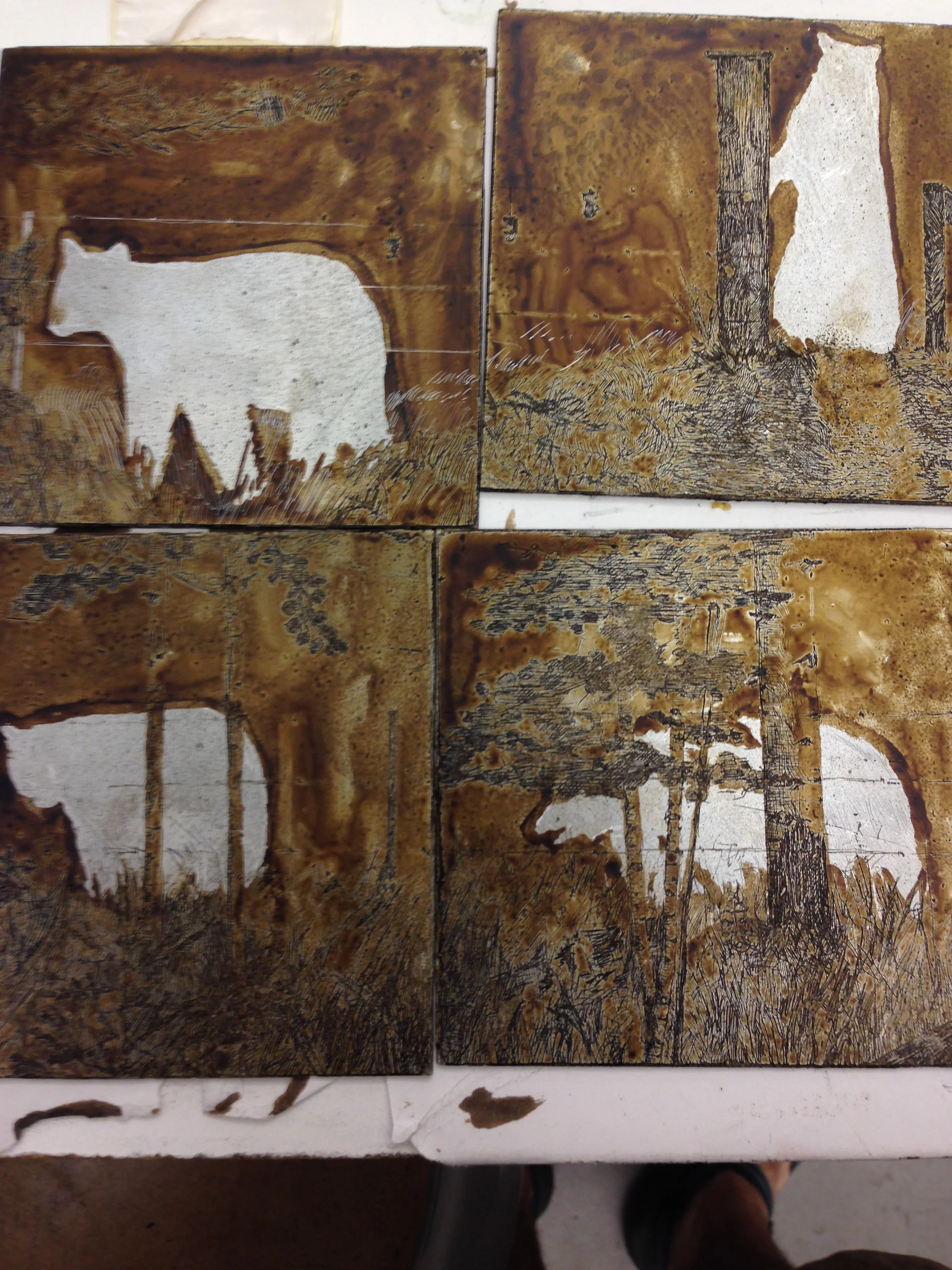

First, a solo show in Midland TX

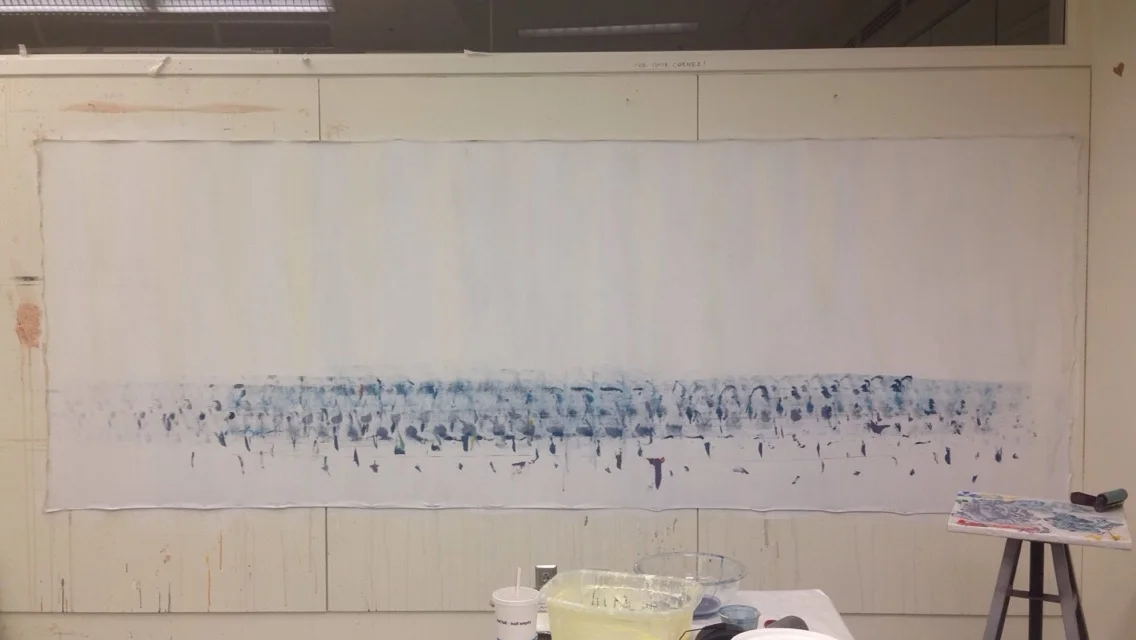

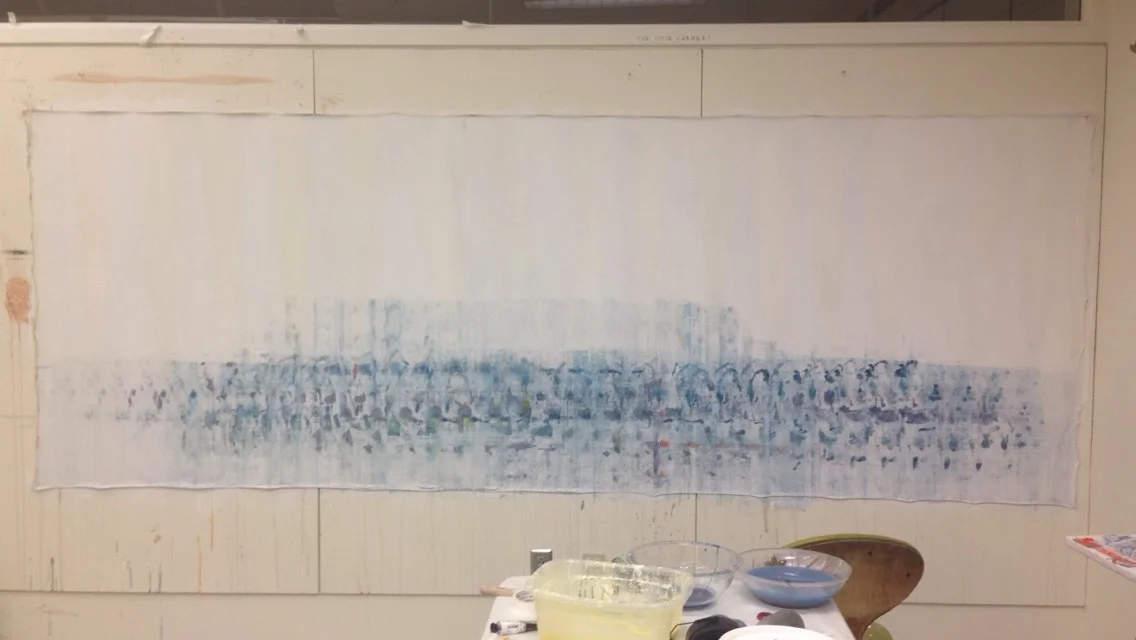

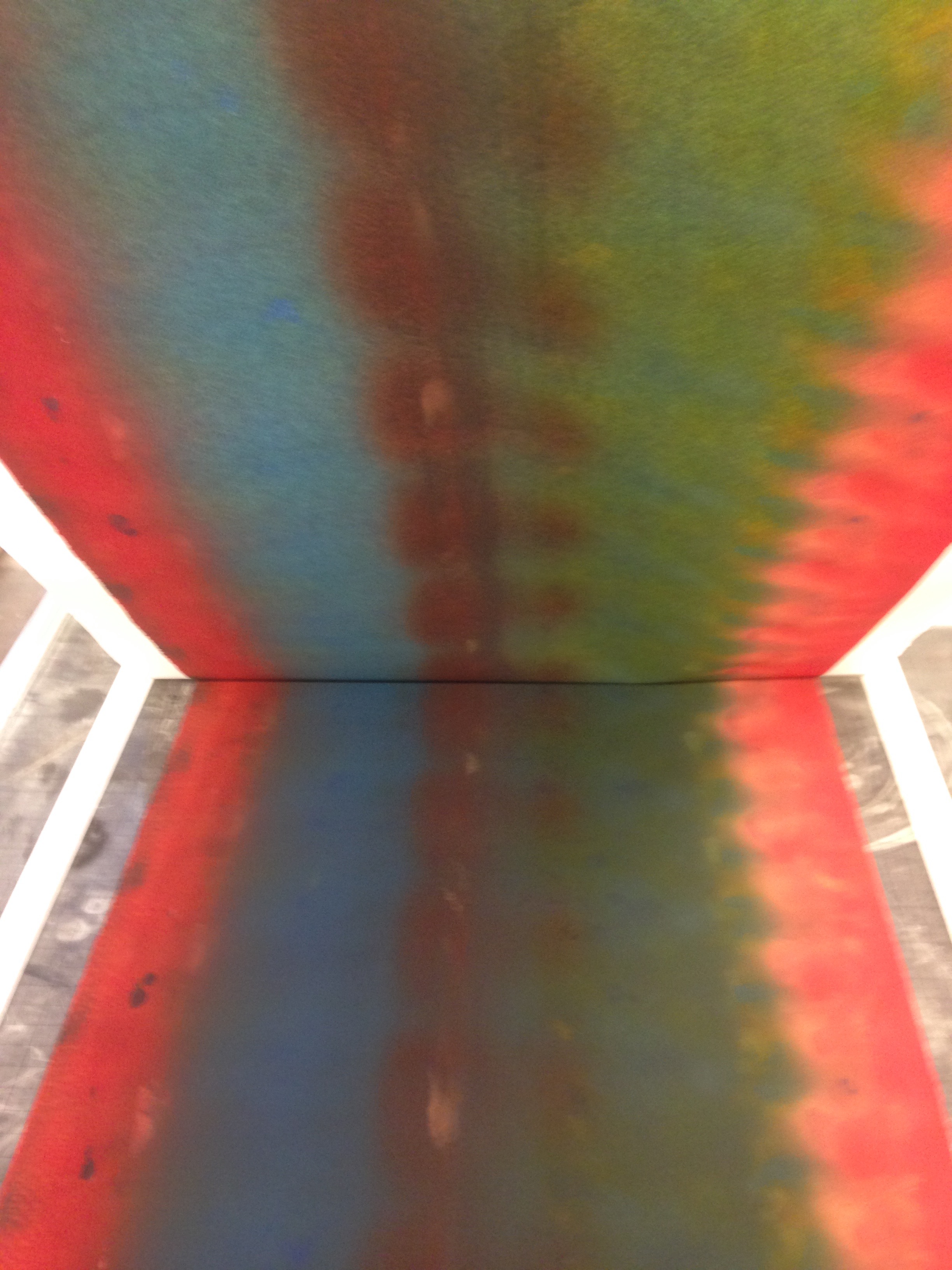

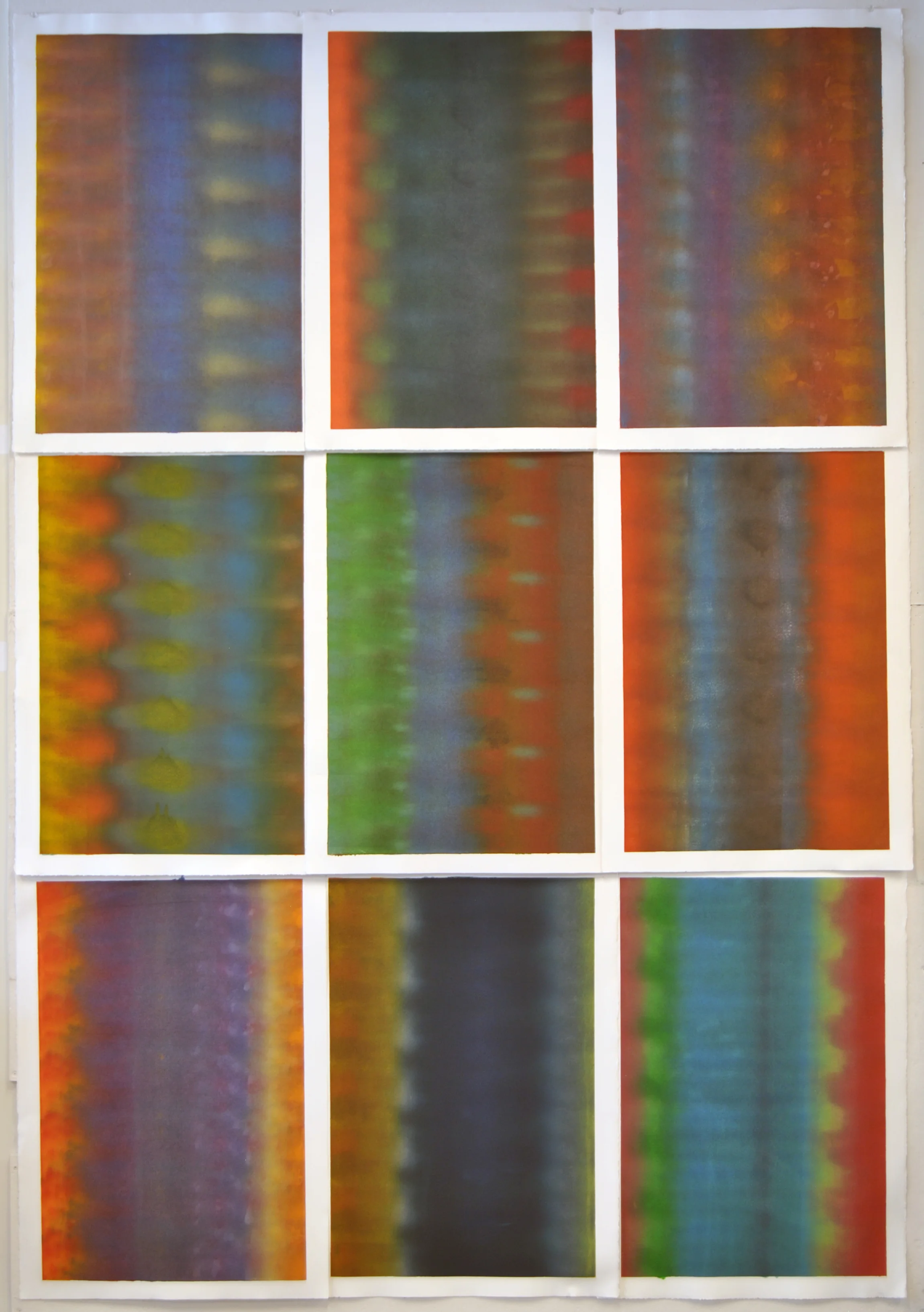

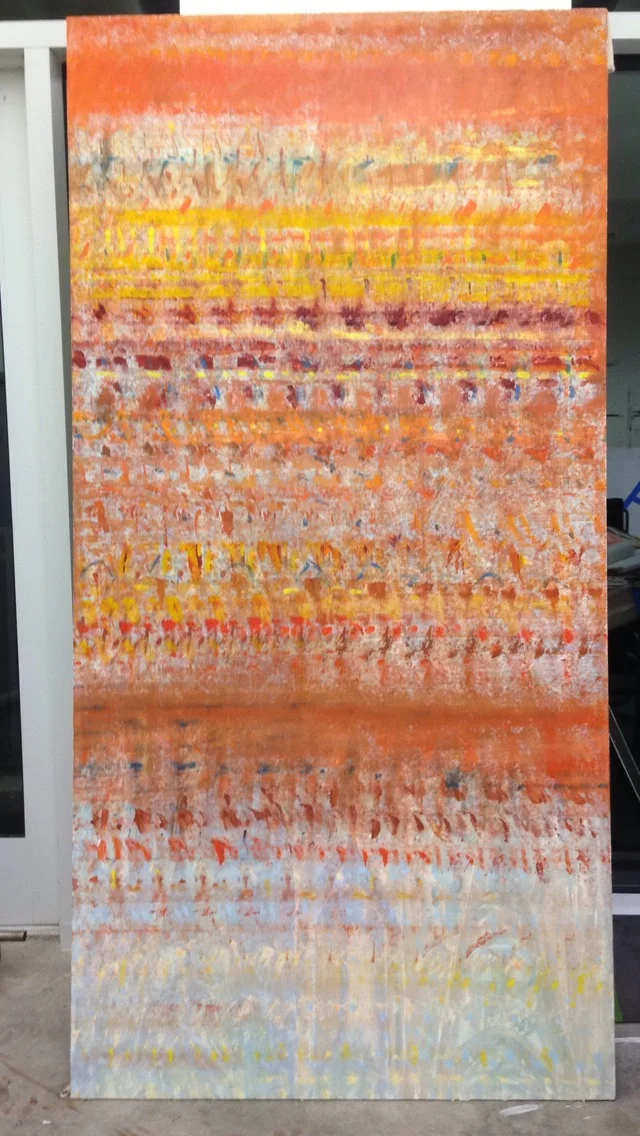

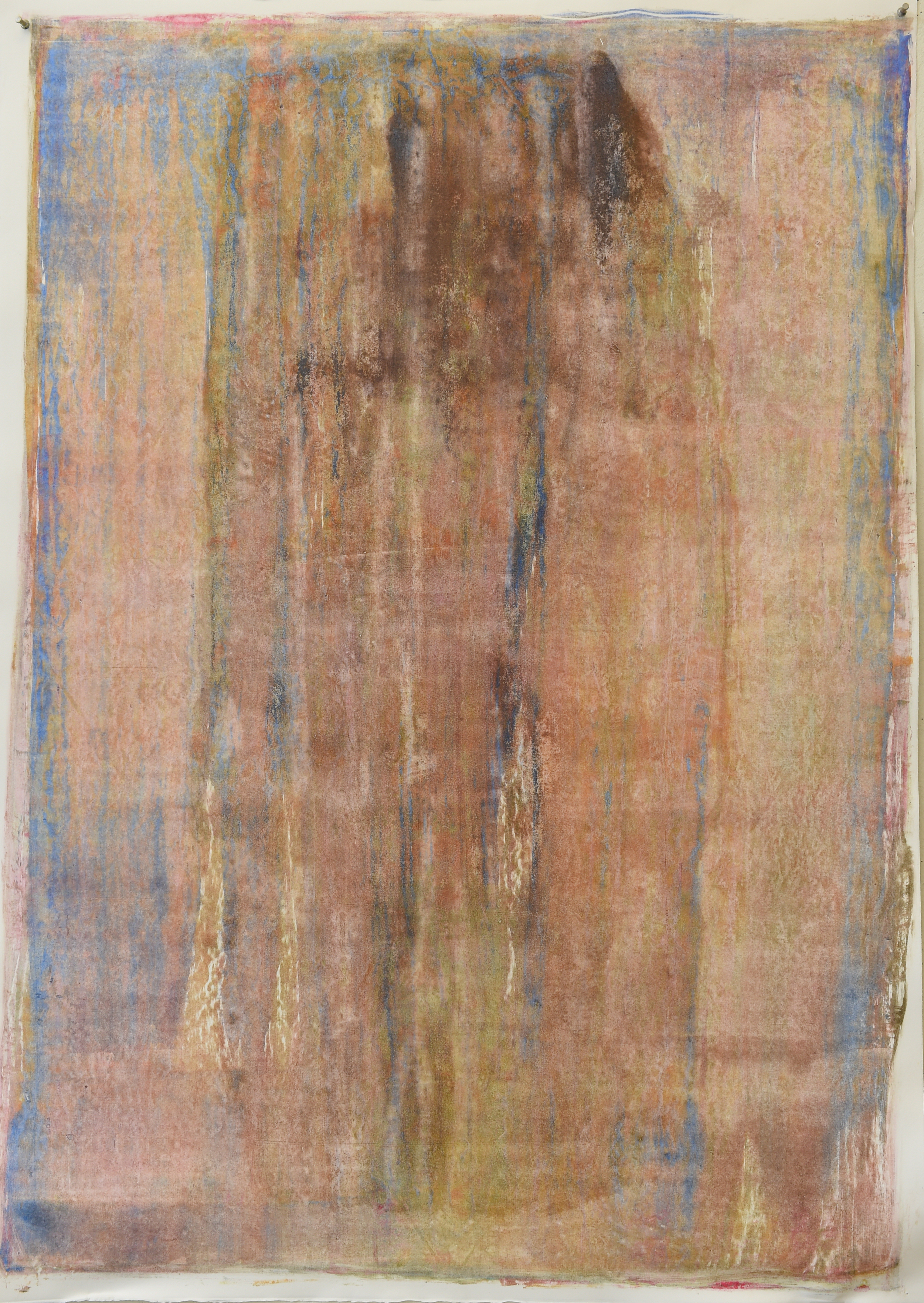

Place was my solo show at Baker Schorr Fine Art from August 27 - September 28. You can click to see the catalog for the show .

Place was the result of several years of work and reflection on recapturing and reviving places that are important to me. I showed several acrylic paintings and works on paper. If you are curious, I made a video about my process and influences . Baker Schorr has been a huge support to me and continues to represent my work.

Several pieces are still available and you can see them on my site on the Available Now page.

What did I look at?

Artists like Suzan Frecon , Julie Mehretu , and Richard Pousette-Dart fueled my art in 2020, and if you’re on Twitter, there’s a great list of bots that comb through the archives of museums and institutions and show work that’s rarely visible to the public.

This Charles Burchfield painting at the Hunter Museum in Chattanooga had me hooked. McKenna and I went several times in 2020 and I always wanted to hang around this one. The dynamic rending of space in the middle coupled with the sharp crescent marks throughout makes this painting pulse with natural energy.

Gateway to September

1946-1956

watercolor on paper

42 x 56 in

I looked at lots of pencil and charcoal drawings. I dug into Wyeth & Sargent a lot. Wyeth gets a lot of flak (“Moving your eye” across his paintings, Peter Schjeldahl wrote, was “like sledding on dirt”). But his drawings to me have captivating trust and fervor. I would also defend most of his paintings.

from the ‘Helga’ Drawings

1975

pencil on paper

24 x 31 in (two sections)

from the ‘Helga’ Drawings

Andrew Wyeth

1972

pencil on paper

18 x 24 in

Two Men in Biblical Costume, possibly for ‘David Mourning Saul and Jonathan’

John Singer Sargent

1895-1900

charcoal on blue laid paper

23 3/4 x 18 1/8 in

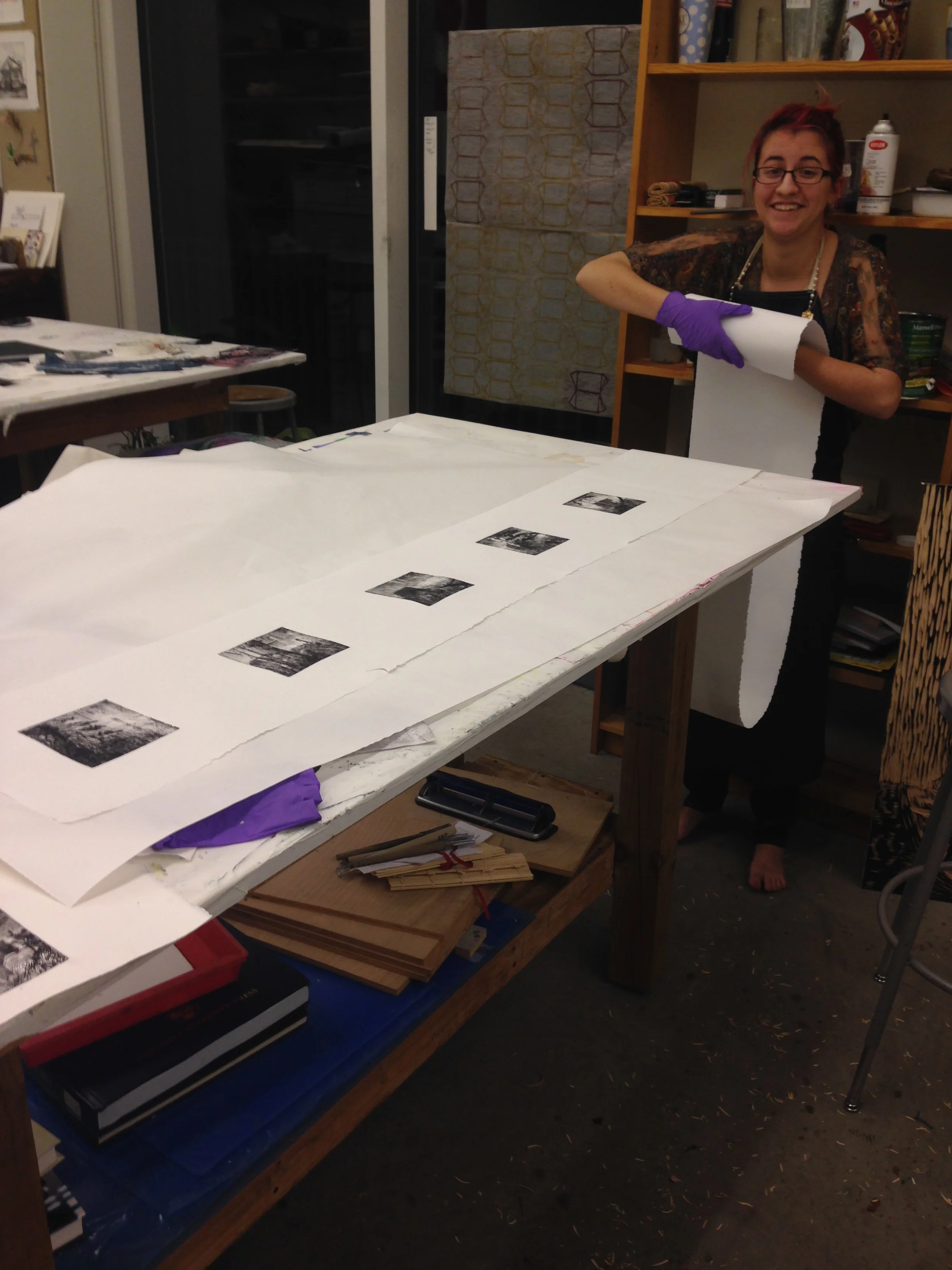

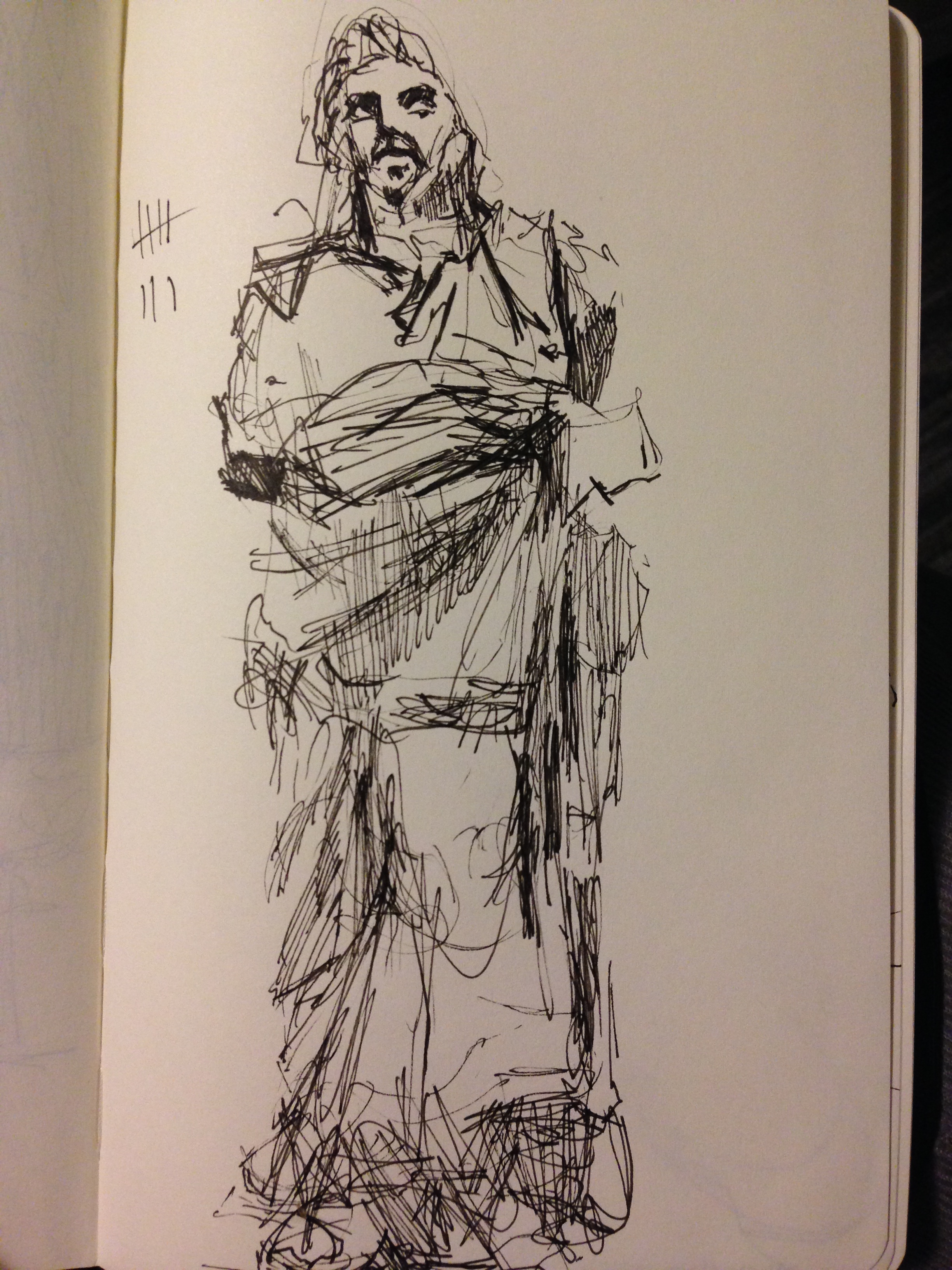

2020 was a big drawing year for me. Lots of sketches of trees, dogs, friends, fish, & football players.

I looked at this old curtain and door a lot. A story for another day.

Who I’m following

On Instagram, @dain_studio, @majaruz, and @theodora_allen were just a few must-follows in 2020.

4AM Gwanju

Dain Lim (@dain_studio on instagram)

2019

oil on linen

162 x 112 cm

Finally, I read, among other things:

Philip Guston’s Collected Writings ,

this great interview with artist Susan Frecon ,

and Wendell Berry’s essay The Work of Local Culture .

I’d love to discuss any of those things with you, or hear what you’re reading.

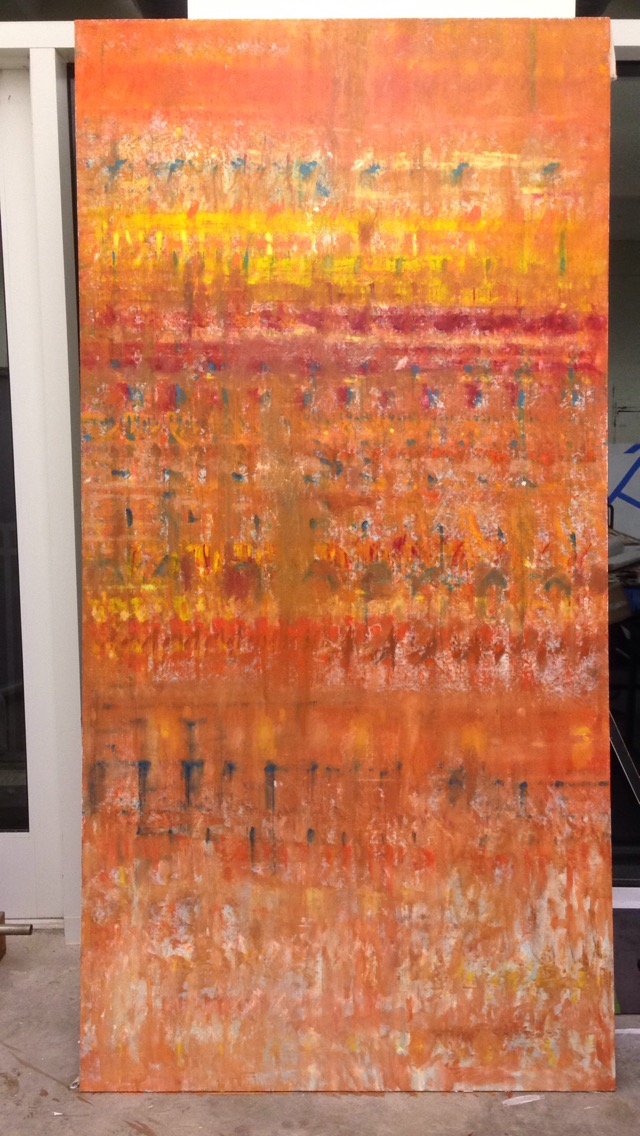

What’s Next

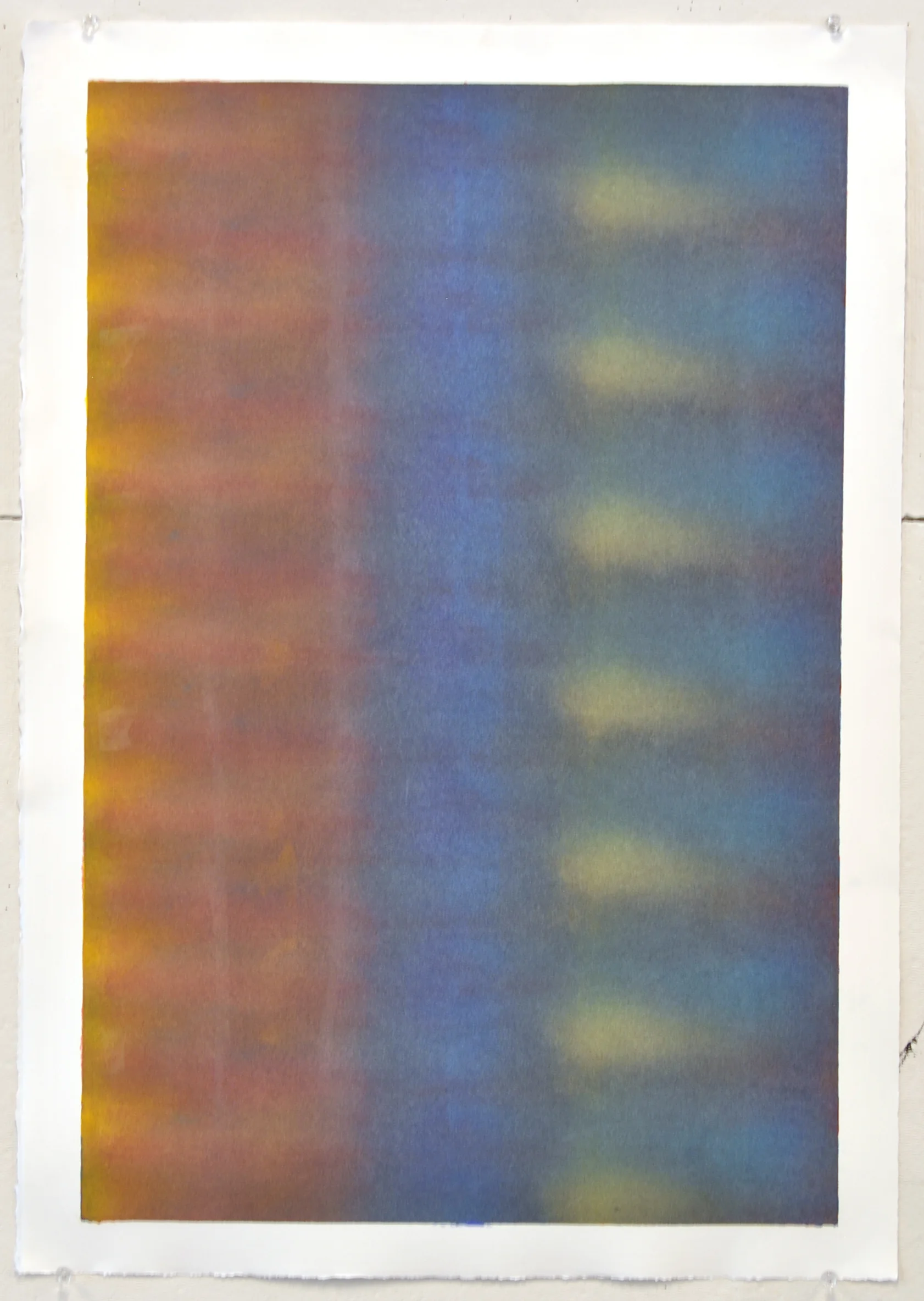

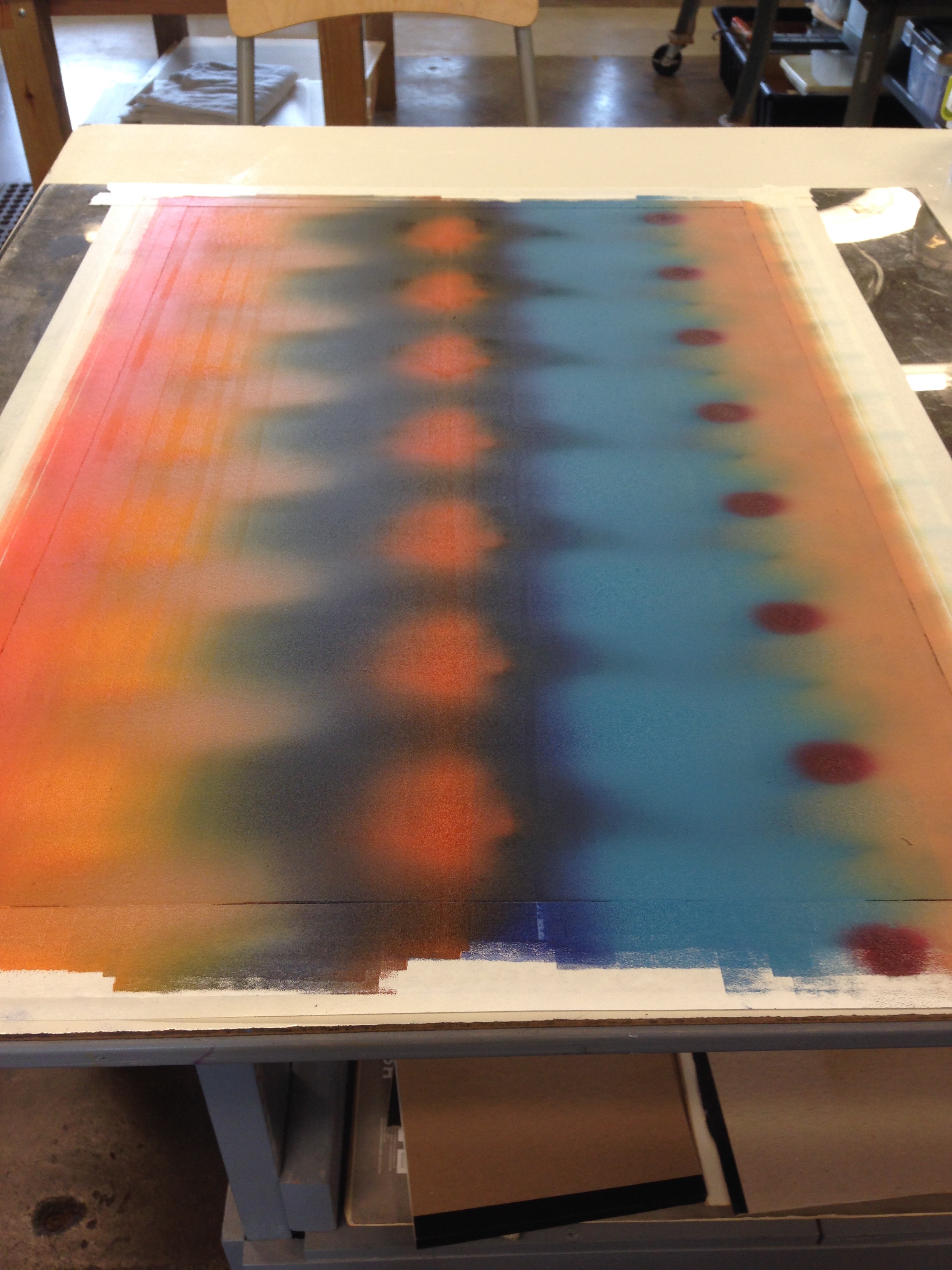

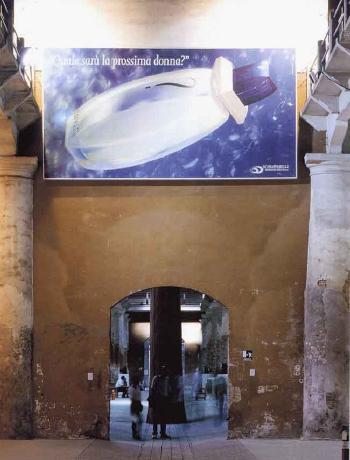

‘Goshen’ or Midnight Spirit

2020

acrylic on canvas

30 x 48 in

I plan on sending more emails this year. I’d love for you to stay subscribed and check out what’s new on my site.